Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin disorder that can be easily treated. This condition is a red, scaly, itchy rash most commonly seen on the scalp, sides of the nose, eyebrows, eyelids, skin behind the ears, and middle of the chest. Other areas, such as the navel (belly button), buttocks, skin folds under the arms, auxillary regions, breasts, and groin, may also be involved.

Your doctor will likely be able to determine whether you have seborrheic dermatitis by examining your skin. He or she may scrape off skin cells for examination (biopsy) to rule out conditions with symptoms similar to seborrheic dermatitis, including:

Dandruff appears as scaling on the scalp without redness. Seborrhea is excessive oiliness of the skin, especially of the scalp and face, without redness or scaling. Patients with Seborrhea may later develop Seborrheic Dermatitis. Seborrheic Dermatitis has both redness and scaling.

This condition is most common in three age groups - infancy, when it's called cradle cap, middle age, and the elderly. Cradle cap usually clears without treatment by age 8 to 12 months. In some infants, Seborrheic Dermatitis may develop only in the diaper area where it could be confused with other forms of diaper rash. When Seborrheic Dermatitis develops at other ages it can come and go. Seborrheic Dermatitis may be seasonally aggravated particularly in northern climates; it is common in people with oily skin or hair, and may be seen with acne or psoriasis. A yeast-like organism may be involved in causing Seborrheic Dermatitis.

Seborrheic Dermatitis may get better on its own, but with regular treatments, the condition improves quickly.

There is no way to prevent or cure Seborrheic Dermatitis. However, it can be controlled with treatment.

Medicated shampoos, creams and lotions are the main treatments for seborrheic dermatitis. Your doctor will likely recommend you try home remedies, such as over-the-counter dandruff shampoos, before considering prescription remedies. If home remedies don't help, talk with your doctor about trying these treatments.

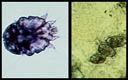

Scabies is an infestation of the skin by the human itch mite. The tiny mites burrow into the upper layer of the skin where it lives and lays its eggs. It has infested humans for at least 2,500 years. It is often hard to detect, and causes a fiercely itchy skin condition. Dermatologists estimate that more than 300 million cases of scabies occur worldwide every year. The condition can strike anyone of any race or age, regardless of personal hygiene. The good news is that with better detection methods and treatments, scabies does not need to cause more than temporary distress.

The microscopic mite that causes scabies can barely be seen by the human eye. Being a tiny, eight-legged creature with a round body, the mite burrows in the skin. Within several weeks, the patient develops an allergic reaction causing severe itching; often intense enough to keep sufferers awake all night.

Human scabies is almost always caught from another person by close contact. It could be a child, a friend, or another family member. Everyone is susceptible. Scabies is not a condition only of low-income families and neglected children, although, it is more often seen in crowded living conditions with poor hygiene.

Attracted to warmth and odor, the female mite burrows into the skin, lays eggs, and produces toxins that cause allergic reactions. Larvae, or newly hatched mites, travel to the skin surface, lying in shallow pockets where they will develop into adult mites. If the mite is scratched off the skin, it can live in bedding for up to 24 hours or more. It may take up to a month before a person will notice the itching, especially in people with good hygiene and who bathe regularly.

The earliest and most common symptom of scabies is intense itching, especially at night. Little red bumps like hives, tiny bites, or pimples appear. In more advanced cases, a rash can spread slowly over a period of weeks or months and the skin may be crusty or scaly.

Scabies skin mite is about 0.4mm, just visible to the human eye

The scabies mite is very small, about the size of the tip of a needle and very difficult to see. It’s white to creamy-white in color. It has eight legs and a round body, which you can see if the mite is magnified. Scabies prefers warmer sites on the skin such as skin folds, where clothing is tight, between the fingers or under the nails, on the elbows or wrists, the buttocks or belt line, around the nipples, and on the penis. Mites also tend to hide in, or on, bracelets and watchbands, or the skin under rings. In children, the infestation may involve the entire body including the palms, soles, and scalp. The child may be tired and irritable because of loss of sleep from itching or scratching all night.

Bacterial infection may occur due to scratching. In many cases, children are treated because of infected skin lesions rather than for the scabies itself. Although treatment of bacterial infections may provide relief, recurrence is almost certain if the scabies infection itself is not treated.

Your healthcare provider must order a cream that contains a medicine called permethrin to treat scabies. The cream is applied to your whole body below your head, including the hands, palms, and soles of the feet.

In children with scabies, the cream may need to be applied to the scalp. Be sure that skin is clean, cool and dry before applying the cream.

Permethrin cream is left on the skin for eight to 14 hours and then washed off. (The cream is most often applied at night and washed off in the morning.)

Ivermectin is another option for treating scabies. This is an antiparasitic pill given in a single dose, followed by a second dose one to two weeks later.

If you’re pregnant or lactating, you shouldn’t use ivermectin. If your child weighs less than 35 pounds (15 kilograms), they shouldn’t use ivermectin.

Your provider might also suggest antihistamines, which can be taken by mouth and as a cream, to relieve itching. Your provider will also treat any type of infection that may be present.

The mites that cause scabies are killed after one treatment. The treatment doesn’t need to be repeated unless the infection doesn’t go away or comes back.

The itching may take two to four weeks to go away, even though the mites have been killed.

Red bumps on the skin should go away within four weeks after treatment.

You can prevent spreading scabies by:

Yes. You can get scabies any time that you come into close contact with an infected person.

No, scabies won’t go away on its own. If you don’t treat it, you’ll probably continue to spread the disease to other people. In addition, the constant itching will probably lead to constant scratching and will cause some type of bacterial infection of the skin.

Scabies is treatable, but they can be hard to get rid of completely. Certain forms of scabies are harder to treat, such as the crusted form. In addition, you might need more than one round of treatment to make sure all of the mites are gone.

If you have a rash and it’s so itchy that you can’t sleep, make sure you contact your healthcare provider. You may have scabies, which is an infectious disease. You and other people close to you should be tested and treated. You’ll want to schedule an appointment with Dr. Robinson if you have any kind of skin rash that doesn’t go away and that causes problems for you. Scabies, like many other types of red itchy rashes, can be treated successfully.

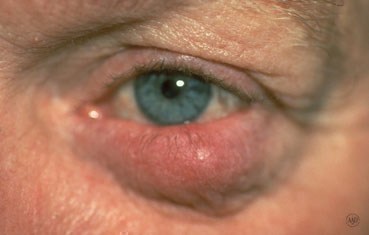

Rosacea is a common skin disease that causes redness, papules, and swelling on the face. Often referred to as adult acne, rosacea frequently begins as a tendency to flush or blush easily. It may progress to persistent redness in the center of the face that may gradually involve the cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose. The eyes, ears, chest, and back may also be involved. With time, small blood vessels and tiny pimples begin to appear on and around the reddened area; however, unlike acne, there are no blackheads.

When rosacea first develops, the redness may come and go. Some people may flush or blush and never form pustules or papules. Small dilated vessels may also be present. However, when the skin doesn't return to its normal color, and when other symptoms such as pimples and enlarged blood vessels become visible, it's best to seek advice from a board-certified dermatologist. The condition may last for years, rarely reverse itself, and can become worse without treatment.

Small red bumps, some of which may contain pus, appear on the face. These may be accompanied by persistent redness and the development of many tiny blood vessels on the surface of the skin.

In more advanced cases, a condition called rhinophyma may develop. The oil glands enlarge causing a bulbous, red nose, and puffy cheeks. Thick bumps may develop on the lower half of the nose and nearby cheeks. Rhinophyma occurs more commonly in men.

Anyone can get Rosacea. It is more common in fair skinned adults between the ages of 30 and 50. Since it may be associated with menopause, women are affected more often than men and may likely have an extreme sensitivity to cosmetics. In people of color, studies show that early symptoms can often be missed and may be under diagnosed because dark skin can mask facial redness. Few children get rosacea, but it is worth considering if the signs and symptoms are there.

Tips for Rosacea Patients

Many people with Rosacea are unfamiliar with it and do not recognize it in its early stages. Identifying the disease is the first step to controlling it. Self-diagnosis and treatment are not recommended since some over-the-counter skin products may make the problem worse.

Dermatologists often recommend a combination of treatments tailored to the individual patient. These treatments can stop the progress of rosacea and sometimes reverse it.

The key to successful management of Rosacea is early diagnosis and treatment. Rosacea can be treated and controlled if medical advice is sought in the early stages. When left untreated, Rosacea will get worse and may be more difficult to treat.

Pruritus is an itch or a sensation that makes a person want to scratch. Pruritus can cause discomfort and be frustrating. If it is severe, it can lead to sleeplessness, anxiety, and depression. The exact cause of an itch is unknown. It is a complex process involving nerves that respond to certain chemicals like histamine that are released in the skin, and the processing of nerve signals in the brain. Pruritus can be a part of skin diseases, internal disorders, or due to faulty processing of the itch sensation within the nervous system.

There are many skin diseases like urticaria (hives), varicella (chicken pox), and eczema which may have itching associated with a rash. Some skin conditions only have symptoms of pruritus without having an obvious rash. Dry skin can itch, especially in the winter, with no visual signs of a rash. Some parasitic infestations such as scabies and lice may be very itchy. Itchy, pigmented moles may be a sign of a malignant change.

Pruritus may be a manifestation of an internal condition. The most common example is kidney failure. Some types of liver disease like hepatitis, thyroid disease including both hyper (too much) and hypo (too little) thyroid hormone levels, some blood disorders such as lymphomas, iron deficiency anemia, polycythemia vera, multiple myeloma, and neurologic conditions such as pinched nerves and post herpetic neuralgia can cause itch. Infectious diseases like HIV can cause severe itching.

Varicella

Eczema

Scabies

Often the dermatologist will be able to diagnose these conditions with an examination; however, to determine a specific cause of the itch, a blood test, skin scraping, or biopsy may be needed to help make the diagnosis. If the itch is due to a skin disease such as hives or eczema, treatment of the skin disease, itself, with prescription topical medications and/or oral antihistamines generally relieves the itch. If the itch is secondary to an internal disease, patients may require treatment of the disease, oral medication, or occasionally ultraviolet light therapy to relieve the itch.

Sometimes, the dermatologist will prescribe a cooling topical lotion or cream and/or an oral medication to relieve the itch. Pruritus is often disrupting and difficult to control but usually responds well to treatment. While a specific identifying cause for the itch may not be found, an appropriate work-up to exclude internal disease should be completed.

Although there are many causes for pruritus, some basics apply to most treatments:

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are the most common cause of allergic reactions in the United States. Each year 10 to 50 million Americans develop an allergic rash after contact with these poison plants.

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac grow almost everywhere in the United States, except Hawaii, Alaska, and some desert areas in the Western U.S. poison ivy usually grows east of the Rocky Mountains and in Canada. Poison oak grows in the Western United States, Canada, Mexico (western poison oak), and in the Southeastern states (eastern poison oak). poison sumac grows in the Eastern states and southern Canada.

In the West, this plant may grow as a vine but usually is a shrub. In the East, it grows as a shrub. It has three leaflets to form its leaves in the shape of an oak tree leaf.

Grows as a vine in the East, Midwest and South. In the far Northern and Western United States, Canada and around the Great Lakes, it grows as a shrub. Each leaf has three leaflets.

Grows in standing water in peat bogs in the Northeast and Midwest and in swampy areas in parts of the Southeast. Each leaf has seven to 13 leaflets.

Poison Plant rash is an allergic contact dermatitis caused by contact with oil called urushiol. Urushiol is found in the sap of poison plants like Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, and Poison Sumac. It is colorless or pale yellow oil that oozes from any cut or crushed part of the plant, including the roots, stems, and leaves. After exposure to air, urushiol turns brownish-black. Damaged leaves look like they have spots of black enamel paint making it easier to recognize and identify the plant. Contact with urushiol can occur in three ways:

When urushiol gets on the skin, it begins to penetrate in minutes. A reaction appears usually within 12 to 48 hours. There is severe itching, redness, and swelling, followed by blisters. The rash is often arranged in streaks or lines where the person brushed against the plant. In a few days, the blisters become crusted and take 10 days or longer to heal.

Poison plant dermatitis can affect almost any part of the body. The rash does not spread by touching it, although it may seem to when it breaks out in new areas. This may happen because urushiol absorbs more slowly into skin that is thicker such as on the forearms, legs, and trunk.

Sensitivity develops after the first direct skin contact with urushiol oil. An allergic reaction seldom occurs on the first exposure. A second encounter can produce a reaction which may be severe. About 85 percent of all people will develop an allergic reaction when adequately exposed to poison ivy. This sensitivity varies from person to person. People who reach adulthood without becoming sensitive have only a 50 percent chance of developing an allergy to poison ivy. However, only about 15 percent of people seem to be resistant.

Identifying the poison ivy plant is the first step in avoiding the rash. The popular saying of leaves of three, let it be; is a good rule of thumb for Poison Ivy and Poison Oak, but is only partly correct. A more exact saying would be leaflets of three, beware of me; because each leaf has three leaflets. Poison sumac, however, has a row of paired leaves. The middle or end leaf is on a longer stalk than the other leaves. This differs from most other three-leaf look alikes.

Poison Ivy has different forms. It grows as vines or low shrubs. Poison Oak, with its oak-like leaves, is a low shrub in the East and can be a low or high shrub in the West. Poison sumac is a tall shrub or small tree. The plants also differ in where they grow. Poison Ivy grows in fertile, well-drained soil. Western Poison Oak needs a great deal of water, and Eastern Poison Oak prefers sandy soil but sometimes grows near lakes. Poison Sumac tends to grow in standing water, such as peat bogs.

These plants are common in the spring and summer. When they grow, there is plenty of sap and the plants bruise easily. The leaves may have black marks where they have been injured. Although Poison Ivy rash is usually a summer complaint, cases may occur in winter when people are cleaning their yards and burning wood with urushiol on it, or when cutting Poison Ivy vines to make wreaths.

It is important to recognize these toxic plants in all seasons. In the early fall, the leaves can turn colors such as yellow or red when other plants are still green. The berry-like fruit on the mature female plants also changes color in fall, from green to off-white. In the winter, the plants lose their leaves. In the spring, Poison Ivy has yellow-green flowers.

Prevent the misery of Poison Ivy by looking out for the plant and staying away from it. You can destroy these plants with herbicides in your own backyard, but this is not practical elsewhere. If you are going to be where you know poison ivy likely grows, wear long pants, long sleeves, boots, and gloves. Remember that the plant's nearly invisible oil, urushiol, sticks to almost all surfaces, and does not dry. Do not let pets run through wooded areas since they may carry home urushiol on their fur. Because urushiol can travel in the wind if it burns in a fire, do not burn plants that look like Poison Ivy.

Barrier skin creams such as a lotion containing bentoquatum offer some protection before contact with Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, or Poison Sumac. Over-the-counter products prevent urushiol from penetrating the skin. Ask your dermatologist for details.

If you think you've had a brush with Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, or Poison Sumac, follow these simple ste

Scratching Poison Ivy blisters will spread the rash.

False. The fluid in the blisters will not spread the rash. The rash is spread only by urushiol. For instance, if you have urushiol on your hands, scratching your nose or wiping your forehead will cause a rash in those areas even though leaves did not contact the face. Avoid excessive scratching of your blisters. Your fingernails may carry bacteria that could cause an infection.

Poison Ivy rash;

False. The rash is a reaction to urushiol. The rash cannot pass from person to person; only urushiol can be spread by contact.

Once allergic, always allergic to Poison Ivy.

False. A person's sensitivity changes over time, even from season to season. People who were sensitive to Poison Ivy as children may not be allergic as adults.

Dead Poison Ivy plants are no longer toxic.

False. Urushiol remains active for up to several years. Never handle dead plants that look like Poison Ivy or use a weed wacker as it will aerosolize the poisonous oils.

Rubbing weeds on the skin can help.

False. Usually, prescription cortisone preparations are required to decrease the itching.

One way to protect against poison ivy is by keeping yourself covered outdoors.

True. However, urushiol can stick to your clothes, which your hands can touch, and then spread the oil to uncovered parts of your body. For uncovered areas, barrier creams are sometimes helpful. Learn to recognize poison ivy so you can avoid contact with it.

Poison Oak

Poison Sumac (wet marshy ares)

Pityriasis Rosea is a rash that occurs most commonly in people between the ages of 10 and 35, but may occur at any age. The rash can last from several weeks to several months. Usually there are no permanent marks as a result of this condition, although some darker-skinned persons may develop long-lasting flat brown spots that eventually fade. It may occur at anytime of year, but Pityriasis Rosea is most common in the spring and fall.

Pityriasis rosea usually begins with a large, scaly, pink patch on the chest or back, which is called a herold or mother patch. It is frequently confused with ringworm, but antifungal creams do not help because it is not a fungus.

Within a week or two, more pink patches appear on the chest, back, arms, and legs. Patches may also occur on the neck, but rarely on the face. The patches are oval and may form a pattern over the back that resembles the outline of a Christmas tree. Sometimes the disease can produce a very severe and widespread skin eruption. About half the patients will have some itching, especially when they become warm. Physical activities like jogging and running, or bathing in hot water, may cause the rash to temporarily worsen or become more obvious. There may be other symptoms including fatigue and aching. The rash usually fades and disappears within six to eight weeks, but can sometimes last much longer.

The cause is unknown. Pityriasis Rosea is not a sign of any internal disease, nor is it caused by a fungus, a bacteria, or an allergy. There is recent evidence suggesting that it may be caused by a virus since the rash resembles certain viral illnesses, and occasionally a person feels slightly ill for a short while just before the rash appears. However, this has not been proven. Pityriasis rosea does not seem to spread from person to person and it usually occurs only once in a lifetime.

Pityriasis rosea affects the back, neck, chest, abdomen, upper arms, and legs, but the rash may differ from person to person making the diagnosis more difficult. The numbers and sizes of the spots can also vary, and occasionally the rash can be found in an unusual location such as the lower body, or on the face. This usually occurs in older individuals. Fungal infections, like ringworm, may resemble this rash. Reactions to certain medications, such as antibiotics, water pill, and heart medications can also look the same as Pityriasis Rosea.

The dermatologist may order blood tests, scrape the skin, or take a sample from one of the spots (skin biopsy), to examine under a microscope in order to make the diagnosis.

Pityriasis rosea often requires no treatment and it usually goes away by itself. However, treatment may include external or internal medications for itching and soothing medicated lotions and lubricants may be prescribed. Lukewarm rather than hot baths may be suggested. Ultraviolet light treatments given under the supervision of a dermatologist may be helpful.

Occasionally, anti-inflammatory medications such as corticosteroid may be necessary to stop itching or make the rash go away. Patients should be reassured that this disease is not a dangerous skin condition even if it occurs during pregnancy.

Remember that Pityriasis Rosea is a common skin disorder and is usually mild. Most cases usually do not need treatment and fortunately, even the most severe cases eventually go away.

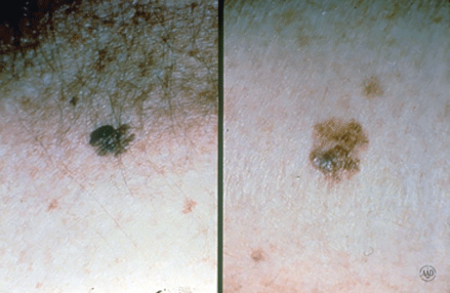

Everyone has moles, sometimes 40 or more. Most people think of a mole as a dark brown spot, but moles have a wide range of appearance. At one time, a mole in a certain spot on the cheek of a woman was considered fashionable. These were called "beauty marks." Some were even painted on. However, not all moles are beautiful. They can be raised from the skin and very noticeable, they may contain dark hairs, or they may be dangerous.

Moles can appear anywhere on the skin. They are usually brown in color but can be skin colored and various sizes and shapes. The brown color is caused by melanocytes, special cells that produce the pigment melanin. Moles probably are determined before a person is born. Most appear during the first 20 years of life, although some may not appear until later. Sun exposure increases the number of moles, and they may darken. During the teen years and pregnancy, moles also get darker and larger and new ones may appear. Each mole has its own growth pattern. The typical life cycle of the common mole takes about 50 years. At first, moles are flat and tan like a freckle, or they can be pink, brown or black in color, Over time, they usually enlarge and some develop hairs. As the years pass, moles can change slowly, becoming more raised and lighter in color. Some will not change at all. Some moles will slowly disappear, seeming to fade away. Others will become raised far from the skin. They may develop a small "stalk" and eventually fall off or are rubbed off.

Recent studies have shown that certain types of moles have a higher-than-average risk of becoming cancerous. They may develop into a form of skin cancer known as malignant melanoma. Sunburns may increase the risk of melanoma. People with many more moles than average (greater than 100) are also more at risk for melanoma.

Moles are present at birth in about 1 in 100 people. They are called congenital nevi. These moles may be more likely to develop a melanoma than moles which appear after birth. Moles known as dysplastic nevi or atypical moles are larger than average (usually larger than a pencil eraser) and irregular in shape. They tend to have uneven color with dark brown centers and lighter, sometimes reddish, uneven border or black dots at edge. These moles often run in families. People with dysplastic nevi may have a greater chance of developing malignant melanoma and should be seen regularly by a dermatologist to check for any changes that might indicate skin cancer. Those susceptible should also learn to do regular self-examinations, looking for changes in the color, size or shape of their moles or the appearance of new moles. Sunscreen and protective clothing should be used to shield moles from sun exposure. Recognizing the early warning signs of malignant melanoma is important. Remember the ABCDs of melanoma when examining your moles: Read more here for Dr. Robinson in the News on Moles.

Melanoma is the most common type of cancer for young adults 25 to 29 years old, and the second most common type for adolescents and young adults 15-29 years old. Melanoma is a cancer of the pigment producing cells in the skin, known as melanocytes. Cancer is a condition in which one type of cell grows without limit in a disorganized fashion, disrupting and replacing normal tissues and their functions, much like weeds overgrowing a garden. Normal melanocytes reside in the outer layer of the skin and produce a brown pigment called melanin, which is responsible for skin color. Melanoma occurs when melanocytes become cancerous, and then grow and invade other tissues.

Melanoma begins on the surface of the skin where it is easy to see and treat. If given time to grow, melanoma can grow down into the skin, ultimately reaching the blood and lymphatic vessels, and spread around the body (metastasize), causing life-threatening illness. It is curable when detected early, but can be fatal if allowed to progress and spread. The goal is to detect melanoma early when it is still on the surface of the skin.

It is not certain how all cases of melanoma develop. Understanding what causes melanoma and whether you’re at high risk of developing the disease can help you prevent it or detect it early when it is easiest to treat and cure.

However, it is clear that excessive sun exposure, especially severe blistering sunburns early in life, can promote melanoma development. There is evidence that ultraviolet radiation used in indoor tanning equipment may cause melanoma. The risk for developing melanoma may also be inherited.

Anyone can get melanoma, but fair-skinned sun-sensitive people are at a higher risk. Since utraviolet radiation from the sun is a major culprit, people who tan poorly, or burn easily are at the greatest risk.

In addition to excessive sun exposure throughout life, people with many moles are at an increased risk to develop melanoma. The average person has around 30 moles, and most are without significance; however, people with more than 50 moles are at a greater risk. In addition to the number of moles, some people have moles that are unusual and irregular looking. These moles (nevi) are known as dysplastic or atypical moles. People with atypical moles are at increased risk of developing melanoma. Melanoma also runs in families. If a relative such as a parent, aunt or uncle had melanoma, other blood relatives are at an increased risk for melanoma.

The following factors help to identify those at risk for melanoma:

Anyone can develop melanoma, but people with one or more of the risk factors are more likely to do so. Annual skin examinations by a board-certified dermatologist can truly be life saving.

To help you find melanoma and other skin cancers early, dermatologists encourage everyone to learn the following:

The ABCDEs of melanoma

Learn to recognize a possible melanoma by learning these 5 warning signs.

How to perform a skin self-exam

Watch this short video to learn how to check your own skin for signs of melanoma and other skin cancers.

An estimated 2-3% of Americans suffer from excessive sweating of the underarms, or of the palms and soles of the feet. Sweating is embarrassing, it stains clothes, ruins romance and complicates business and social interactions. Severe cases can have serious practical consequences as well, making it hard for people who suffer from it to hold a pen, grip a car steering wheel or shake hands.

If left untreated these problems may continue throughout life. We can help!

Once other medical conditions have been ruled out, we offer a range of exciting treatment options – from prescription products to in-office treatments – to manage this condition. Dr. Robinson has many happy patients who were treated for Hyperhidrosis.

Although neurologic, endocrine, infectious, and other systemic diseases can sometimes cause hyperhidrosis, most cases occur in people who are otherwise healthy. Heat and emotions may trigger hyperhidrosis in some, but many who suffer from hyperhidrosis sweat nearly all their waking hours, regardless of their mood or the weather.

Through a systematic evaluation of causes and triggers of hyperhidrosis, followed by a judicious, stepwise approach to treatment, many people with this annoying disorder can sometimes achieve good results and improved quality of life.

The approach to treating excessive sweating generally proceeds as follows:

Schedule an office visit to discuss your concerns and skincare goals with Dr. Robinson and the office visit cost will be applied to the future cost for the "consulted procedure". The "consulted procedure" must be completed within 30 days of your consult visit.

The herpes simplex virus (HSV) causes blisters and sores often around the mouth, nose, genitals, and buttocks, but they can occur almost anywhere on the skin. HSV infections can be very annoying because they may reappear periodically. The sores may be painful and unsightly. For chronically ill people and newborn babies, the viral infection can be serious, but rarely fatal. There are two types of HSV - Type 1 and Type 2.

Often referred to as fever blisters or cold sores, infections are tiny, itchy, clear, fluid-filled blisters, often grouped together. They most often occur on the face.

Cold sores are caused by certain strains of the herpes simplex virus (HSV). HSV-1 usually causes cold sores. HSV-2 is usually responsible for genital herpes. But either type can spread to the face or genitals through close contact, such as kissing or oral sex. Shared eating utensils, razors and towels might also spread HSV-1.

Cold sores are contagious even if you don't see the sores. Cold sores spread from person to person by close contact, such as kissing.

There are two kinds of infections - primary and recurrent. Although most people get infected when exposed to the virus, only 10 percent will actually develop sores. The sores of a primary infection appear two to twenty days after contact with an infected person and can last from seven to ten days.

The number of blisters varies from a single to a group of blisters. Before the blisters appear, the skin may itch, sting, burn, or tingle. The blisters can break as a result of minor injury, allowing the fluid inside the blisters to ooze, crust & scab. Eventually, crusts fall off, leaving slightly red, healing skin.

The sores from the primary infection heal completely and rarely leave a scar. However, the virus that caused the infection remains in the body. It moves to nerve cells where it remains in a resting state.

People may then have a recurrence either in the same location as the first infection or in a nearby site. The infection may recur every few weeks or not at all.

Children under 5 years old may have cold sores inside their mouths and the lesions are commonly mistaken for canker sores. Canker sores involve only the mucous membrane and aren't caused by the herpes simplex virus.

Recurrent infections tend to be mild. They can be set off by a variety of factors including fever, sun exposure, a menstrual period, trauma (including surgery), or nothing at all.

Cold sores generally clear up without treatment. See your doctor if:

There's no cure for cold sores, but treatment can help manage outbreaks. Prescription antiviral pills or creams can help sores heal more quickly. And they may reduce the frequency, length and severity of future outbreaks.

Link to Domeboro instruction sheet